Implants that require a steady source of power but don’t need wires are an idea whose time has come.

Now, for therapies that require multiple, coordinated stimulation implants, their timing has come as well.

Rice University engineers who developed implants for electrical stimulation in patients with spinal cord injuries have advanced their technique to power and program multisite biostimulators from a single transmitter.

A peer-reviewed paper about the advance by electrical and computer engineer Kaiyuan Yang and his colleagues at Rice’s Brown School of Engineering won the best paper award at the IEEE’s Custom Integrated Circuits Conference, held virtually in the last week of April.

The Rice lab’s experiments showed an alternating magnetic field generated and controlled by a battery-powered transmitter outside the body, perhaps on a belt or harness, can deliver power and programming to two or more implants to at least 60 millimeters (2.3 inches) away.

The implants can be programmed with delays measured in microseconds. That could enable them to coordinate the triggering of multiple wireless pacemakers in separate chambers of a patient’s heart, Yang said.

“We show it’s possible to program the implants to stimulate in a coordinated pattern,” he said. “We synchronize every device, like a symphony. That gives us a lot of degrees of freedom for stimulation treatments, whether it’s for cardiac pacing or for a spinal cord.”

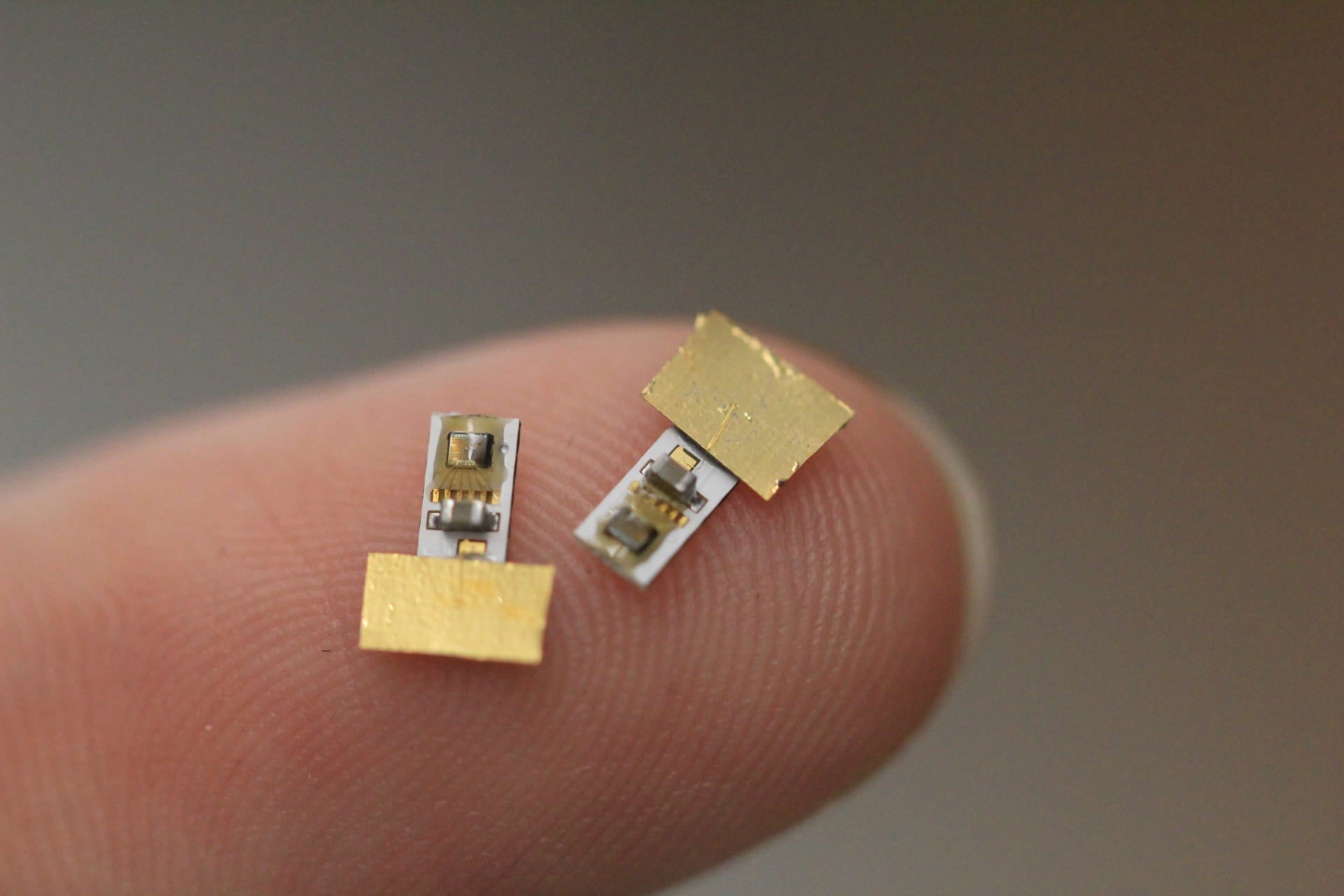

The lab tested its tiny implants, each about the size and weight of a vitamin, on tissue samples, live hydra vulgaris and in rodents. The experiments proved that over at least a short distance, the devices were able to stimulate two separate hydra to contract and activate a fluorescent tag in response to electrical signals, and to trigger a response at controlled amplitudes along a rodent’s sciatic nerve.

“There’s a study on spinal cord regeneration that shows multisite stimulation in a certain pattern will help in the recovery of the neuro system,” Yang said. “There is clinical research going on, but they’re all using benchtop equipment. There are no implantable tools that can do this.”

The lab’s devices, called MagNI (for magnetoelectric neural implants) were introduced early last year as possible spinal cord stimulators that didn’t require wires to power and program them. That means wire leads don’t have to poke through the skin of the patient, a situation that would risk infection. The other alternative, as used in many battery-powered implants, is to replace them via surgery every few years.

Rice graduate student Zhanghao Yu is lead author of the paper. Co-authors are graduate students Joshua Chen, Yan He, Fatima Alrashdan and Amanda Singer, staff specialist Benjamin Avants and Jacob Robinson, an associate professor of electrical and computer engineering and bioengineering. Yang is an assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering.

The National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering and National Science Foundation supported the research.